This month I’m encouraging people to donate to and/or get involved with Black Girls CODE, an organization in the Bay Area working to encourage girls of color to become innovators and leaders in STEM fields.

I have to admit I can’t spend very much time on Disney parks-related forums or — even worse — Twitter, because I just don’t have the patience for it. I get all kinds of anxiety when I see adults screaming at each other over which is the most magical novelty popcorn bucket, or starting discussion threads to ask whether the parks are an insultingly hollow shadow of what they used to be, or if they’re just a disgraceful insult to everything that Walt stood for.

And it’s a shame, too, because I have irrationally strong opinions about the parks. If it sounds like I’m mocking the kind of person who goes online to scream about the evils of FastPass, I’m not, because I am that kind of person — we just differ in magnitude. They all seem to be operating at around 15, whereas I’m usually around 11 or 12.

But there are some things that all Disney fans, no matter how obsessive, can agree on… or can we?! There are some ideas that I’ve seen for years treated as just common knowledge among fans, but I disagree with, because I am a rebel and an iconoclast.

Horizons was just okay.

Yeah, I’m coming out guns blazing. Horizons is widely considered to be the best of original EPCOT Center, a masterpiece of “old-school” Imagineering, and the soul of Epcot’s Future World. I definitely don’t think it’s bad, but I’ve never understood the reverence for this attraction over, say, Journey Into Imagination or World of Motion, both of which blew my mind as a teenager.

As someone who went to EPCOT Center quite a few times in the early years, my main memory of Horizons was that it was never open. There seemed to be a ton of preview buzz around it, and it had the coolest park icon and a neat-looking building, so I was pretty excited. The “space” ending film is iconic, and I seem to remember seeing it before I was actually able to go on the ride, so I was already hyped for a senses-shattering simulator experience that probably wasn’t even possible in 1983. But I feel like at least a few years passed before I was finally at the park when it was open and not down for refurbishment.

I have to think that part of the reason I was underwhelmed by the attraction is because it always felt like a survey course in “Intro to Epcot Center Future World 101,” instead of a deep dive. I felt like I’d already seen everything from the ride, in one form or another, in Carousel of Progress, If You Had Wings, World of Motion, Listen to the Land, The Living Seas, Spaceship Earth, and Journey Into Imagination. It was like trying to get excited about the greatest hits album when you’re already at the concert.

The Adventurer’s Club was only really fun for people who love improv.

The Adventurer’s Club was another one of those things that I got hyped about for years before actually seeing it. My family weren’t enthusiastic about bars or nightclubs, so it wasn’t even really an option for me until I went back to Disney World as an adult, by myself. By that point, I believe I’d already heard rumors that it would be closing within a few years, so I went two nights in a row to make sure I got the full effect.

In terms of decoration and theming, it was outstanding, of course. You could try to describe it as “kind of like Trader Sam’s, if it were extended across multiple floors and multiple rooms and actually had enough seating,” which sounds perfect. And the idea of characters walking through the space, interacting with guests; and a drunken, possibly insane old adventurer puppet acting as host of the evening and leading everyone in a toast; and a room full of masks that talk to you and tell stories — it’s all wonderful in theory. But in practice, I’ve got to say that it was corny AF.

It’s here that I should talk about something that’s been a problem for me for as long as I’ve been going to Disney parks, which is literally my entire life. And that’s Improv People. I know many, many great people who love improv and find real joy in watching and/or performing it, and it genuinely makes me happy to see them enjoy it. But in general, people who love improv just cannot understand that not everyone enjoys improv. For some of us, it’s like torture.

When I’m in the audience and a joke bombs, it almost causes me physical pain. I can’t stand those moments of dead time and the look of manic desperation in a performer’s face when they’re trying to come up with the next thing to say. Even when it’s going well, I have the feeling of being trapped in a car going 150 miles an hour and knowing that it could crash and burn at any moment. If I could try to describe what watching, listening to, or ::shudder:: performing improv feels like to me: imagine you’re standing naked on a stage, with your arms tied behind your back, and a spotlight is shining directly on you. Right behind you, someone is standing with his mouth just a couple of inches away from your neck, and you can feel his hot, damp breath on the skin on the back of your neck and behind your ear, as he exhales, “hh-h-h-he-heh-heh-help me.”

People who work in themed entertainment and “immersive theater” tend to be unable to accept that not everyone loves improv as much as they do, so I tend to be put in situations where I’m dragged screaming out of my comfort zone. The Star Wars hotel has me torn between my lifelong love of Star Wars and my intense anxiety at the thought of being trapped in a two-day-long non-stop immersive theater performance. With the Adventurer’s Club, a can’t-fail theme and setting that might as well have been designed specifically for me, still weren’t quite enough to compensate for being surrounded by people who at any moment could assault me with family-friendly “yes, and…”s.

Also, the drinks weren’t any good.

The Grand Fiesta Tour is a criminally underrated delight.

When the Mexico pavilion opened at Epcot, there was a boat ride called El Rio del Tiempo. It used a lot of the same tricks of other modestly-budgeted rides of the time, and it was perfectly pleasant even if you weren’t quite sure whether the market vendor scene was really racist but suspected that it probably was.

With the Grand Fiesta Tour overhaul, it was improved ten thousand times. It added characters and music from The Three Caballeros, which is a no-brainer, and updated all the gags to feature Donald Duck instead of real human Mexican actors and dancers. Somehow, that makes it both more contemporary and also timeless.

I haven’t actually ever heard complaints about replacing the original — which is surprising, since every time they replace an original ride, they get complaints, even with a ride that no one actually liked unironically, like Maelstrom. But there’s rarely a wait for it, and people for the most part call it “cute” instead of acknowledging that it’s a must-see at Epcot.

I would rather ride a Guardians of the Galaxy roller coaster than an hour-long advertisement for fossil fuels.

When Disney at the D23 Expo last year announced that there was going to be a massive overhaul of Epcot’s Future World, my reaction was that I was surprised I wasn’t more upset about it. I’m as eager to throw a tantrum about Disney ruining my childhood as the next guy, but in this case the changes for Future World were at least 10 years overdue.

The big complaints I’ve seen are people calling it “IPCot,” for basing everything on Disney-owned intellectual property, instead of basing everything on original characters and concepts.

I want to be more sympathetic here, because most of my favorite Disney attractions are originals — Space Mountain, The Haunted Mansion, Expedition Everest, most of the original Future World. When Epcot first opened, Imagineering was pretty adamant about distinguishing it from the Magic Kingdom, which meant no attractions based on Disney movies and none of the familiar characters in the park. You eventually got Figment from Journey Into Imagination as your cartoon mascot, and you had to be satisfied with that.

Except guests weren’t really satisfied with that, and Epcot developed a reputation for being boring “edutainment” instead of a fun theme park. Even as someone who loved the original Epcot, I think fans (and some Imagineers) can be a little too precious about the “purity” of the experience; I don’t think it’s particularly shallow or dumbing things down if someone on their vacation would rather ride roller coasters than pay to hear corporations talking about the wonders of industrial agriculture or our not-at-all-worrisome dependence on fossil fuels.

Now, I’ve softened on this one a little bit. At first, I assumed that people complaining about trading corporate sponsorships for Moana and Guardians of the Galaxy themed attractions were just being unrealistically nostalgic. But I did see a friend explain his take: as a lover of World’s Fairs, he appreciated that Epcot uniquely had the feeling of a permanent World’s Fair. Part of that is the optimism of corporations working in the public interest; the presentations weren’t just crass advertisements, but sincere excitement over the things that could be made possible. I do like that idea, and I have to concede that these changes will leave Epcot feeling less like a unique place, and more like, say, California Adventure. Not so much of an overarching theme anymore, except “Disney also owns all of these properties, too.”

But I’m not completely sold on it. As a teenage insomniac who never missed Late Night, I idolized David Letterman. And I took his anti-corporate stick-it-to-The-Man schtick to heart (even though in retrospect, it’s almost offensively phony and insincere). So I think that the rotating screen display of the original Universe of Energy pre-show was one of the coolest things I’ve ever seen, and the dinosaur section was such a fantastic homage to/extension of classic Disney and the Disneyland railroad, and the Ellen’s Energy Adventure version is still one of the cleverest and most charming ways of presenting educational material that I’ve ever seen. But it’s still an Exxon ad. Even with the best of intentions, Disney presenting pavilions dedicated to promoting Nestle, Kraft, General Electric, or Exxon in 2020 would just come across as really tone deaf.

Also, I think the Mission Breakout overhaul of the Tower of Terror in California Adventure is phenomenal. The original ride at Hollywood Studios is one of my favorite things that Disney’s ever done, so I’ll be complaining if they ever mess with that one. But the California redo is better in every possible way (except for the outside of the building, which is still weird). It’s relentlessly fun, a perfect use of the ride tech — since it was never really a “free fall” ride, this has it hover up and down at each scene — and feels like it should’ve been this way all along. Plus the details around the queue are fantastic, and the character shows with Peter Quill and Gamorra leading dance-offs outside the ride are fantastic. So Disney knows how to make Guardians of the Galaxy attractions, and a show-heavy spinning coaster can’t not be fun.

Besides, the lines are going to be so long after the parks open back up and the ride opens, it’ll be a few years before any of us get a chance to ride it anyway.

Epcot embracing its theme parkness isn’t necessarily a bad thing. I would like to see Journey Into Imagination redone in the spirit of the original. But Disney’s had a pretty strong run of movies for several years now, with more hits than misses. If it became a Zootopia pavilion or something, it’d be disappointing but still far from the worst thing to happen to that attraction.

Galaxy’s Edge is the right way to do Star Wars in a theme park

This isn’t that controversial, really, since people liked Galaxy’s Edge, and Rise of the Resistance seems to be universally loved. (Early noise about Galaxy’s Edge being a “failure” seems to be a combination of clickbait wanting Disney to fail, and judging it in comparison to unrealistically high expectations). There are two pretty consistent criticisms I’ve heard:

First, that there aren’t enough droids and aliens wandering around. I agree with that. It’s all done so well that it’s actually jarring to be reminded of what’s missing. It’s noticeable that the droids and ships are trapped behind fences. It seems like there need to be aliens in the cantina. Especially considering how the land is practically “defined” not by its rides but by the walk-around interactions, it seems like an especially good investment here than it would be elsewhere.

The second criticism I hear often is that they should’ve set the land during the time period of the original trilogy, and on a familiar planet like Tatooine. I don’t agree with that at all. I mean, if I were just being consistent, I’d say that Imagineering shouldn’t be so precious with its “world-building;” just like people in Epcot and Animal Kingdom wanted to see Mickey Mouse, people in Star Wars Land want to buy T-shirts that say “Star Wars” on them. But I honestly believe that this is one of the rare cases where the “normal people won’t notice it” level of detail is actually noticeable in the end product.

Star Wars hasn’t been a sustained hit over 50 years; it’s been a cycle of six or seven years of intense popularity followed by long stretches of not many people caring. The fandom is all over the place — the animated series, video games, comics, novels all have their own super-fans. Any attempt to recreate a fan-favorite location is automatically going to miss the mark for a ton of people, and it’s inevitably going to feel like trying to hit a moving target.

Creating a new location, and having it reference the existing ones, give it a much longer life and just make the universe feel like it has more potential. I can remember being a Star Wars-obsessed teenager watching Return of the Jedi the first time in 1983, and when the opening crawl said that they were going back to Tatooine and to the Death Star, it felt like such a cop-out. A galaxy that seemed infinitely expansive with limitless potential for stories now seemed comically tiny and unimaginative.

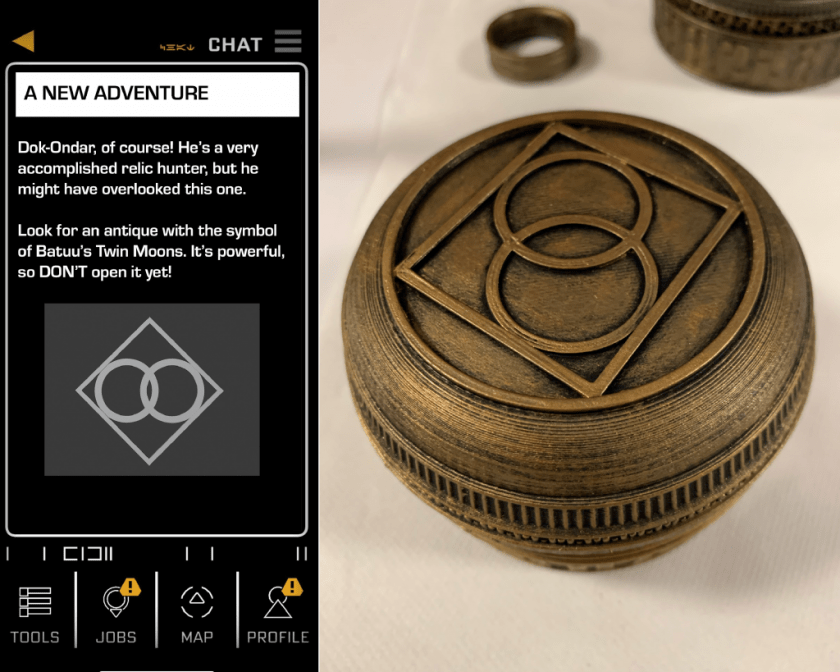

For me, “Batuu” has just the right amount of familiar details, while still feeling like it’s a new place where new stories can happen. It doesn’t need to look like Mos Espa, it just needs to look like Star Wars. That has a ton more potential, because it establishes that Star Wars isn’t any one particular existing “thing;” it’s more a style. I may not be able to define exactly what makes something “Star Wars,” but I know it when I see it.

It was mean-spirited, humorless, and like so much of the 1990s, it was a desperate attempt to be “edgy” and “extreme.” It was completely tone deaf for the Magic Kingdom, and the attempt to “soften” it from being too scary just made it an attraction that was too scary and had a crappy, nasty opening that fried a cute animatronic for laughs. (Muppetvision 3D showed the right way to do that gag, several times over). It’s well known that it was originally intended to be an Alien-themed attraction, but it completely ignored that Alien had an actual hero in the form of Ripley. So it ended up just nihilistic and pointless.

Those were dark days, when Disney was trying to play to the lowest common denominator, making fun of the simplest and most obvious criticisms of Disney to make it seem like they were in on the joke. It seems like those days are gone, but I guess as the theme park industry stays competitive, there’s always the risk of falling back into bad habits. I hope Disney keeps thinking of sincerity, happiness, and a childish belief in “magic” as assets of the brand, instead of a liability.